Album download > THE SLIDER on Bandcamp

Album download > THE SLIDER on Bandcamp

THE SLIDER is one of ten pieces of music chosen by Sarah Lucas for BBC Radio 3’s programme Private Passions, broadcast 5 February 2017.

01 BRITTEN – Fanfare for St. Edmondsbury

02 YES – Long Distance Runaround

03 BRITTEN – Sally in our Alley

04 GURNEY – Sleep

05 PURCELL – Tis I that have warm’d ye

06 PURCELL – To Woden thanks we render

07 CAN – Oh Yeah

08 SIMMONS – THE SLIDER

09 BRITTEN – Big Chariot, Songs from the Chinese

10 BRITTEN – Dance Song, Songs from the Chinese

BBC Radio 3, edited broadcast Private Passions – Sarah Lucas. NB not available as the original 1 hour broadcast, for copyright reasons all the music in this stream has been shortened to 1 minute.

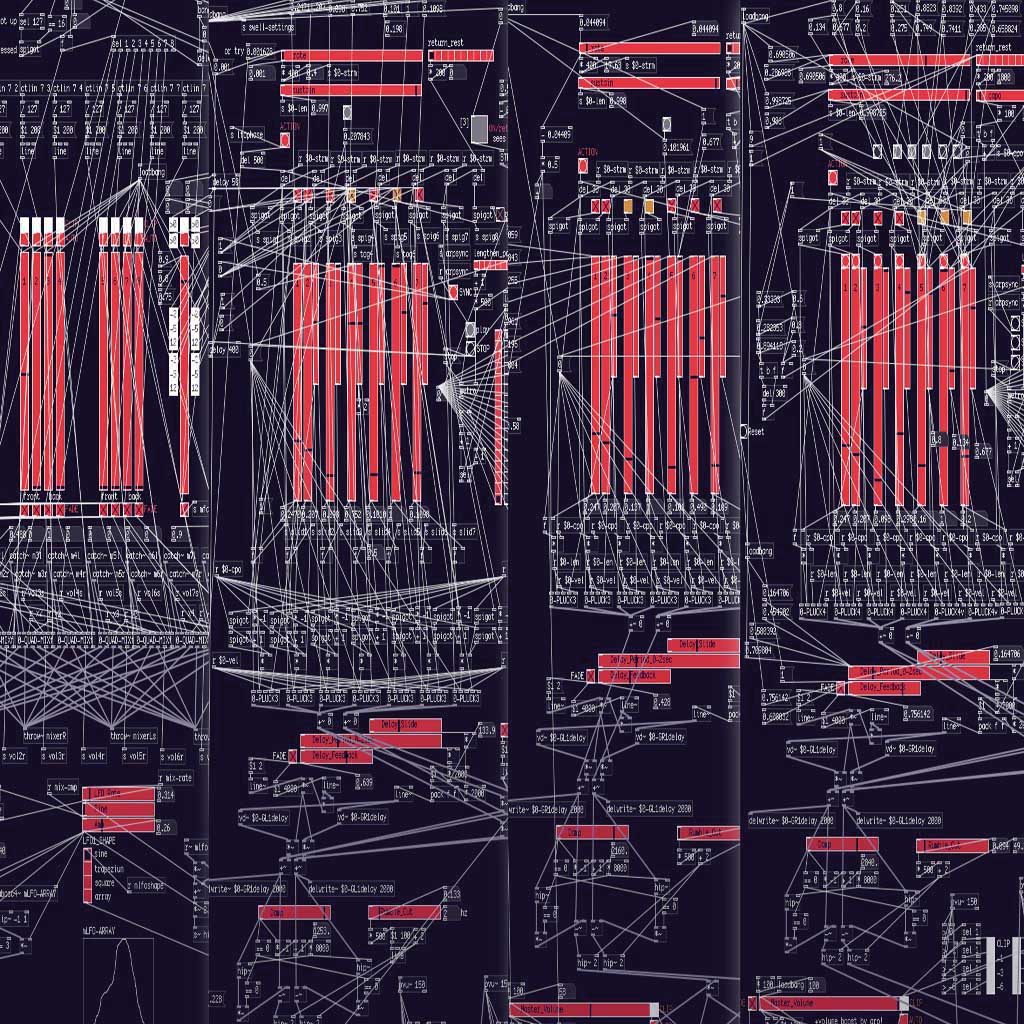

[Above] the NUMBERSTREAM mixer-panner and the three ‘7-string’ slider instruments plucked and bowed in this broadcast.

“It’s like a bunch of grapes!”, Sarah Lucas.

How did ‘THE SLIDER’ originate?

It’s first incarnation was composed in 2011 for a live performance in the then recently unveiled Hoffmann Building at Aldeburgh Music, Snape Maltings, Suffolk, UK. This was the first year of the SNAP group interventions held alongside Aldeburgh Music’s summer Festival programme. SNAP was instigated by the painter Michael Craig-Martin and the sculptor Sarah Lucas, to reintroduce the greater freedom of the original 1960’s festivals organised by Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears – where experiments in sound and visual art were both embraced. It was vital therefore that the computer-based instruments I’d built should be displayed – so their construction and method of playing could be made apparent to the audience: don’t look at me – look at my instrument! I seem to remember a couple of architects closely inspecting the wall-mounted screen, people pointing, and Will Self hovering head and shoulders above everyone else, circumspect. Russell Haswell performed after me, it was one of the first outings for his newly born modular synthesiser.

Why ‘THE SLIDER’?

If the answer isn’t yes, it’s somewhere between this or that, …the slider! Variables make maths interactive, delicate, alive, human. You know the Chinese notion that everything changes – the law of change, if two successive moments are identical – that’s death. Electronic music through it’s ease at utter exactitude of repetition can propagate something akin to rigid industrial farming or the army …and yet quite readily through some inner cross-referencing and transmutable patterns it can otherwise engender the complex balances within wilderness and stimulate psychotropic thought. After one of my performances someone remarked… “When you played last night I closed my eyes and just let the sounds take over in the dark; it felt like your music went into my brain and created new synapses – how mad is that!”. There is a romance and generosity within math …that also circutuitously bears the imprint of the individual imparting the math; density matched by intimacy is always at the forefront of my instrument building and composing.

If you’re ever asked a harsh question, remember: actuality is a slider, it’s all bound up with scale, extremes are important to the actual.

NUMBERSTREAM instruments are not defined by western scales – they are fretless, keyless; open to sliding frequencies – glissando, portamento! A particular slider that is essential to my performances is the rate of actioning ‘strings’. The same instrument can seamlessly transform from being an energetically bowed cello, to a slow deliberately struck piano or guitar – all through a slider; one might say it’s an exercise in ontology. The final part of this piece – ‘THE SLIDER’ exemplifies this, seemingly running out of energy, though actually revealing the full life of notes in their required time – that are otherwise prevented by bowing / rapid re-actioning.

Particular influences?

At the time there were two pieces of music that pervaded the instruments and the composition: Britten’s Sea Interludes from Peter Grimes and Mike Oldfield’s Hergest Ridge. In both cases it was their opening of continuous and elevated ‘fever-pitch’ notes that made their impression, and in the case of Hergest Ridge it was also the record sleeve.

As you know, frequency is simply the perception of a repeating pattern of any from of disruption [or less provocatively, information]. So high-frequency is a pattern of rapidly repeating information, in the visual spectrum this is perceived as violet to ultra-violet – a high-energy that bleaches – that knocks particles into thin air, as opposed to the massaging effect of low-freq infra-red. Sonically the physical results are similar.

“Listened, thanks for that. Very enjoyable whilst trying to find a colour.” Gary Hume.

In terms of density of information, high-frequency is a particular pleasure for me, not only for it’s intrinsic energy but mainly in that it offers a level of microscopic detail that low frequency cannot contain. With concentration it’s something to get one’s mental and perceptual teeth into – within the right now – otherwise you’ll have missed it and be clocking the poverty of low-frequency notes.

I’d just begun to design physical-modelling instruments in Pure Data, previously the instruments were more on the ‘electronic synth’ and haunting side. Physical-modelling endeavours to simulate characteristics of the source object or body that generates the sound, rather than mimicking the resultant sound by modifying existing parameters through educated trial and error. Of course physical-modelling is also an unique starting point. Being free of the original physics it offers novel opportunities. These source objects can be anything from the sea, to aircraft, to actual musical instruments – such as pianos, violins, etc.

I wished to mesh with the venue’s heritage – it was also an influence [Snape Maltings, Britten’s centre for modern classical music] and so these electronic ‘7-string’ instruments built through physical-modelling chimed in well.

Since then I’ve added further NUMBERSTREAM instruments and synthesised environmental sounds, developed the score and have performed the piece many times live, quadraphonically.

Quadraphonically?

Building instruments for live quadraphonic performances and diffusions has become my main area of electroacoustic investigation. Music can be robotic [replaying one’s own memories] or passive [replaying someone else memories], or in terms of it [as vibration] otherwise being an entity with a fresh and active intelligent purpose. Quad enables a space to be inhabited by instruments, encouraging, though I’d say, demanding, the audience to move around and explore the physical environment for an escapade that in some way remaps their mind… …in case you had any doubts.

The ability to introduce further instruments and environmental sounds to a quadraphonic space, does tend to overload a stereo space – where the listener will be located between two speakers. The differences are at least a dimension apart: from 1 dimension – a line in front of you [stereo] to 2 dimensions – upon a plane [quad], or even 3 dimensions – within a space [speakers / the PA placed at different heights]. Quadraphonic PA positioning doesn’t need to be purist [in four corners], the purpose is not the reproduction of a recording, it’s an experimental live performance particular to and tailored to unique spaces. The arrangement of the PA can be freely manipulated, placed in a cross rather than a square, or simply allowing the space to suggest novel locations [behind abandoned rusty cars was one].

There’s been increasing interest in binaural audio – a performance captured with two microphones set into the artificial ears of a physical model of a human head. When the recording is replayed, the frequency modulation and path time produced by the distance apart and folds in the ‘ears’, does marginally flesh-out and warp the recorded performance. Ultimately though it’s a 2nd-hand flattened stereo recapitulation, and cannot be compared to experiencing actual quad with your own ears and vibrations in your bones and deep bodily orifices.

I see this interest in binaural, especially via radio and VR, as an insatiable movement towards true quad; satiable of course with actual quadraphony. Evidently through radio this recording cannot be quadraphonic, though I’ve maintained a very particular stereo character – unusually each instrument is spread across the left-right field [they don’t pan, but rather the width of the instruments are the width of your speaker placement, or room]; if you might be listening on a compact radio or laptop possibly try other means – hi-fi or headphones.

You’ve said this is a new recording?

…yes and a new performance: why edit pre-recorded performances when I can re-perform a composition in current circumstances. Plus I never record to multi-track, the recording is the live mixed-down line-out. That’s what I mean by a recording – even though digital it is a recording [this on the 27th Oct 2016 at 12:27] and can’t be re-mixed or meddled with. For BBC Radio 3’s programme Private Passions I necessarily shortened the score to around 7-minutes – it was originally 18-minutes; along with this I removed synthesised environmental sounds while performing and also placed the instruments within a forward stereo field rather than moving within quadraphonic space [spatial locating joysticks were kept forward!].

Having assembled the math to generate the sound sources – and then the instruments to modify in real-time the parameters of those sources, certainly there is a particular and evident ‘mind behind’ this, but also a human being! The score I follow is open to interpretation, mainly in terms of pitch-change extent and time periods. Some additions were made to instruments, introducing subtle almost indiscernible vibrato in the first section [at about the rate of a 33rpm record], and to the score – where for radio-broadcast the end of a piece may suffer the risk of being faded out or talked over [thankfully though not usually on Radio 3], I added a significant last note – to ensure it would be played to the very end.

In fact this note has now become vital to the composition, so much so I would now not perform it without. This delicate last ‘dang’ as a punctuation mark or struck metal bowl sums and resets everything before; upon it everything both rests and awakens: that note is the private passion! – it’s the start of a smile. Just when you thought this is how it’s going to end, it doesn’t! I’m drawn to the very subtle, yet very powerful.

Why do you think Sarah Lucas chose this piece?

In all variations it’s certainly my classic score; she said…

“It’s like finding yourself outside at night… in front of the heavens… and the whole of reality drops away.”

This brings to mind a scene in a film, perhaps I shouldn’t relate to popular media but why the heck not. You’ll most likely know the film and the sequence: not only is time suspended but curiously that suspension acts on the resuming moment of time afterwards …where all the bullets fall to the ground. This notion of apprehension or apprehending following moments, assists expectation, it’s a seduction; slightly holding time back enables memory and imagination to flood forward and enter perception. Which is tantamount to saying, reality – or the construct of time, can variously affect actuality – or the perception of time.

Or otherwise by Sarah in conversation with Michael Berkeley – here’s a transcript from the Radio3 broadcast :

MB / The next piece is by Julian Simmons, and it’s chosen to evoke the Suffolk countryside around Snape Maltings.

SL / Yes, he originally made this piece of music for an art exhibition, a group show called SNAP a bunch of us did at Snape Malting to coincide with the Festival, and he performed it live in the derelict buildings adjacent to the concert hall.

MB / He sent a note with it, to us, saying that the beginning was inspired by waking up in a Suffolk field, to the violin buzz of millions of insects.

SL / Well the thing about Julian is he’s very… I mean the main reason for staying so much in Suffolk is Julian – as he doesn’t care much for the town …because he’s very interested in the natural world – he’s really tuned-in both visually and in an audio way to the minute things that other people don’t pick up. So he’s very attuned to insects or birds – he can hear mice when I can’t hear them. He can never hear what I’m saying, you know even if I’m right next to him, he’ll say “what?” he’ll get it completely wrong! – but if there’s a mouse squeaking somewhere in the grass he’ll hear that; …you know …he’ll just pick it up.

One thing we should take away from this?

Frequency, High Frequency!

…not only as pitch but also of density – of information.

Frequency.

‘I’d begun to design physical-modelling instruments in Pure Data’ : NUMBERSTREAM instruments

Download > THE SLIDER on Bandcamp